Amyris: from antimalarial to hypergrowth DTC

Amyris may be the first synbio company to have cracked product market fit by selling direct to consumers.

Emerging frontier technologies like synbio are very hard to commercialize. There are no playbooks. Early on, processes are inefficient and expensive.

To come down the cost curve usually requires first hitting product market fit in niche, beachhead markets. I've written about this for solar, lithium ion batteries and historical traction in coal, steel, oil, automobiles, electricity, aluminum and more.

What are the early niche markets for synbio? Therapeutics (bio-based drugs) have strong traction. These are low volume, very high value + margin products where yields don’t matter as much. They often can only be made using bio.

But what other markets help pull demand forward?

Many startups are betting on variety of bio-produced materials, food products, specialty chemicals and more.

Which brings us back to Amyris. It may well have more consumer product traction today than any other synbio company.

Let’s look at why this matters and how this fighter of a company got here.

Summary

(1) the company survived several false starts and pivots over its 19 years and

(2) it now has a playbook for accelerated launched of new consumer brands (and more revenue growth)

(3) as one of the first startups to IPO and commercialize multiple synbio products

Current traction

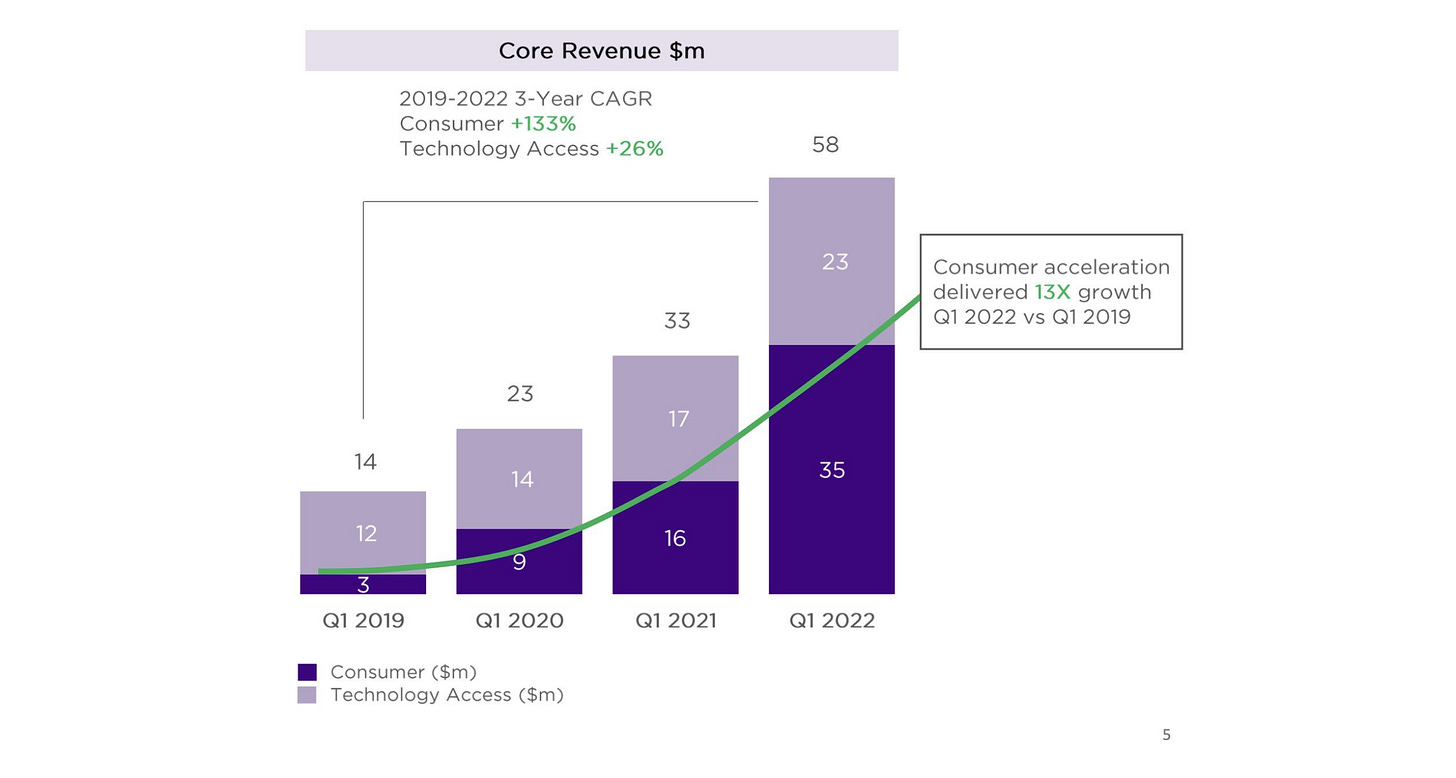

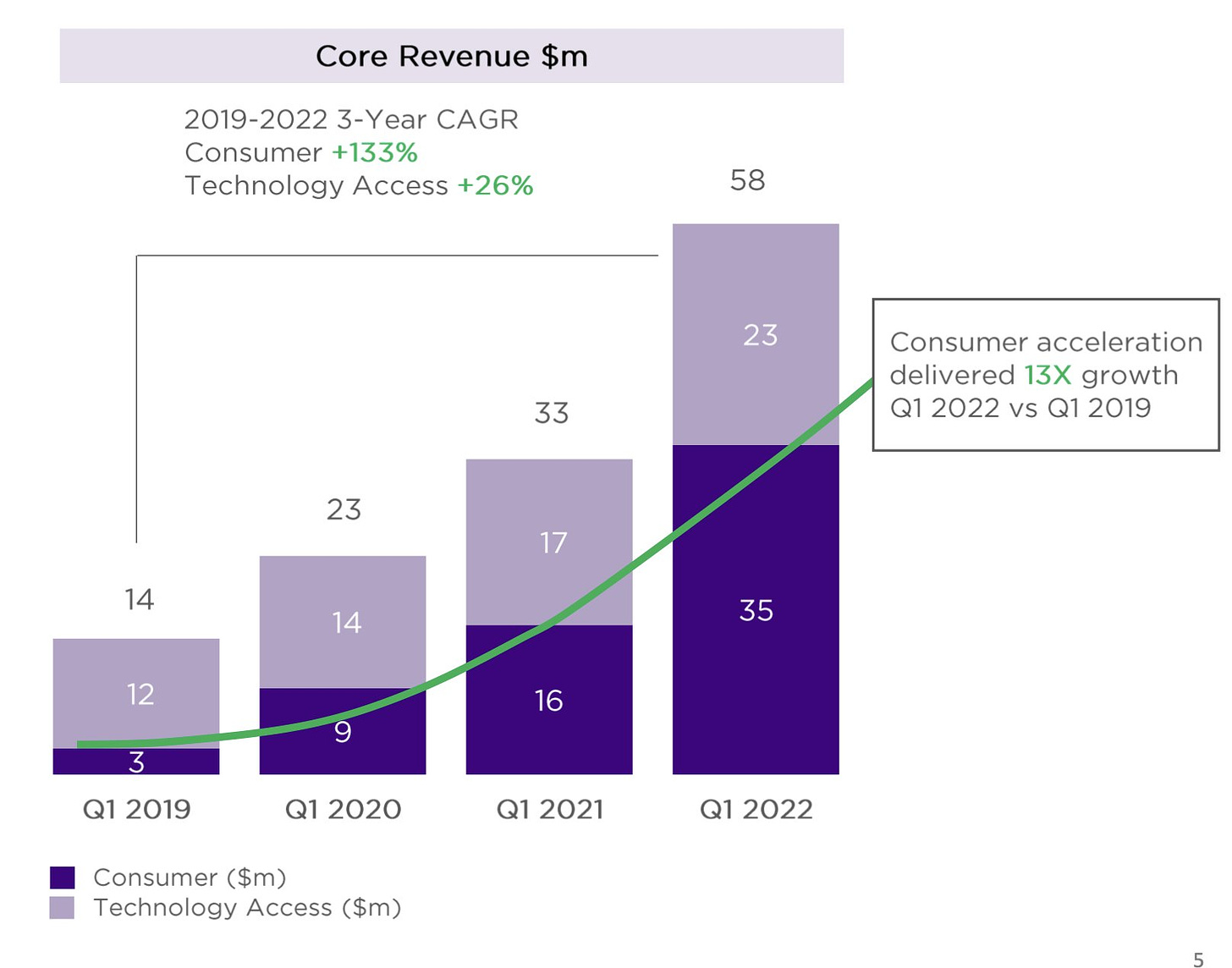

Amyris is growing fast. For the last three years, revenue from their consumer products have grown at 133% CAGR. This might seem like pretty modest numbers for a 19 year old company. But it's remarkable given what it has been through, starting in 2003.

In 2019, as shown below, about 20% of the business was in consumer brands; this year, by contrast, CEO John Melo says that more than half of their revenues will come from them.

“We have been moving to the consumer very, very rapidly. We expect our consumer business to keep doubling every year for the foreseeable future. The consumer side will be somewhere around $130 million this year. That’s off last year being $52 million. It’s a fun place to be.”

- John Melo, CEO, Amyris, 2007-present.

Despite being relatively low on cash, he is very confident about their ability to continue the 133% CAGR growth in their consumer business over the last 4 years.

Early days

The founders, N. Renninger, K. Reiling and J. Newman, were all post docs from the Berkeley lab of metabolic engineering pioneer Jay Keasling.

During the mid 2000s the team had engineered a yeast strain that produced artemisinic acid, a precursor to an anti-malarial drug.

They sold the rights to their artemisinin tech to Sanofi royalty-free.

Then came the biofuels pivot.

Biodiesel and Cleantech 1.0

John Doerr, Vinod Khosla and other VCs invested around then. It seems Khosla had a strong influence in getting the team to focus on diesel:

“Set your sights on diesel,” Khosla told the Amyris team, according to Newman. “It’s the hardest thing you’d want to do, but it’s the biggest market out there, and you’ll build an incredible company.” Finding an alternative to petroleum had the same ring as battling malaria: The world would be better for it. Fast Company

They engineered a strain of yeast to produce farnesene, which can be processed into diesel. Renninger, the founder and CTO until 2012, had multiple farnesene related patents from work at Amyris. To help go to market, they brought on a new CEO, ex BP exec John Melo in 2007.

A year after IPO’ing during the height of cleantech 1.0, Amyris promised 6M liters of farnesene but only produced 1M liters. This was peanuts for Melo coming from O&G. And so he underestimated how hard it would be to scale by selling a commodity as an early niche market.

Amyris also underestimated the challenges with scale up of the first of a kind plant and a pathway to drive costs down. They did manage to lower the cost of making farnesene from $7.8/lt in 2011 to $1.75/lt in 2015 (cash cost). But $6.62/gallon for making a precursor to diesel is a non-starter.

In hindsight, the biofuels pivot was a bad decision.

Melo also ousted cofounders Renninger and Reiling. Things were not looking good.

Finding traction in squalene

Amyris had to pivot away from selling diesel. They focused on selling higher value chemicals. The first molecule would be squalene, a cosmetics ingredient that later became core to its growth.

Amyris could process farnesene into squalene. By 2011, they had secured two contracts for it with distributors to the cosmetics industry. Previously, cosmetics companies had sourced high purity squalene from the livers of deep water sharks.

Amyris had been getting better at making quality farnesene at lower costs, as we mentioned above. They quickly gained traction in the global squalene market. By 2013, only two years after manufacturing at any scale, they supplied 18% of the ~$90M market. Today, only 11 years after commercialization, they have 70% of the market.

For the next few years, Amyris survived where many biofuels startups did not. It generated most of its revenue through selling squalene to cosmetics distributors and companies like Avon, Unilever, and Procter & Gamble.

Going direct to consumers

With these early wins in the squalene market, Amyris started seeing the opportunity to go direct to consumers (DTC). In 2015 it launched Biossance, a brand featuring the chemical in creams and oils. It was the first of Amyris’s own brands available to order online DTC.

The org competencies required for DTC distribution are vastly different to those required for selling diesel. The internal reorg must not have been easy. But it’s starting to pay off now.

On a recent earnings call, Melo claimed Biossance is the fastest growing skincare brand of its scale in North America. Amyris has doubled down on selling to consumers via their own online channels and partners like Sephora and Walmart.

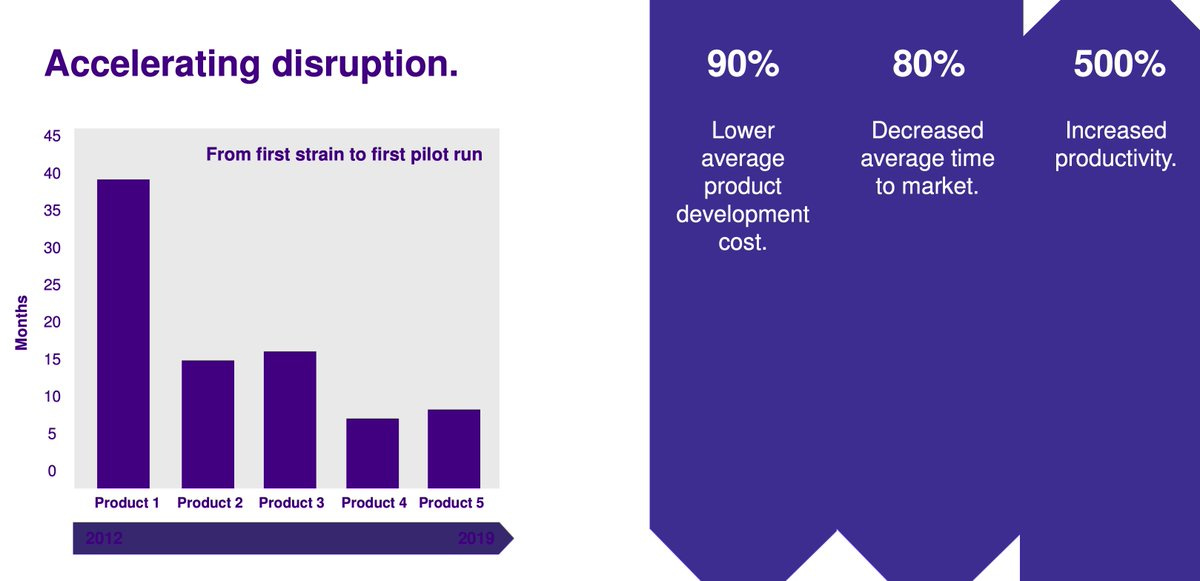

They now have 9 more consumer brands launched or acquired, all since 2017. Accelerated R&D of yeast strains has helped drive 4x faster speed to market as shown below.

Amyris is also much faster today at launching new brands, many of which are seeing significant traction. It now has playbooks and strategies for launching new brands.

Their most successful is JVN which launched last year and cost $2.7M in R&D and launch. It should be profitable within 14 months and do $50M sales this year. That's a remarkable return on investment, in a very short period of time. It took Biossance four years to do as much revenues.

Driving growth from DTC and retail partners has also improved their gross margins to be between 60-70% for consumer brands. They may well be in the early days of

Amyris is an incredible story. They managed to survive and morph into a compnay unrecognizable from its early anti-malarial drug days . Only recently did they find product market fit in an industry that 19 years ago the founders perhaps never would have envisioned.

Fast followers

Synbio startups today looking to scale DTC can do it faster than when Amyris started.

For example, startups like Checkerspot are starting with “DTC native” go to market strategies. Their founders saw promising signs of this whilst working on the consumer team at Solazyme, when most everything else was not going well.

Other synbio startups like Cronos, Arcaea and ZBiotics are all going after high value, low volume beachhead products that can help spin up their growth flywheels.

More to come

Amyris is one of the more interesting case studies I’ve seen so far in how to scale a nascent technology, and a playbook for scaling biotech. Increasingly synbio startups might start as DTC native in the coming years as they see the benefits.

More to come on case studies of different synbio business models as I explore deep tech ideas enabled by clean, cheap energy and other tech tailwinds.

This article is *not* investment advice and I do not own any stock in Amyris.